The disappearance of the Roanoke colonists—often called the Lost Colony—remains one of the most compelling mysteries in early American history. Established in the late 16th century on Roanoke Island (modern-day North Carolina, then part of Virginia), the settlement vanished without leaving behind a clear explanation. Despite centuries of scholarship, archaeology, and speculation, the fate of the men, women, and children of Roanoke continues to provoke debate, inspire folklore, and challenge historians.

Background: England’s First Attempts at Colonization

By the 1580s, Spain dominated much of the Americas. England, eager to challenge Spanish power and secure its own overseas empire, turned to colonization. Sir Walter Raleigh, a favorite of Queen Elizabeth I, was granted a charter in 1584 to explore and colonize lands in North America. Early Reconnaissance (1584–1585) Raleigh dispatched exploratory voyages led by Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe. They reported fertile land, friendly Native peoples, and strategic coastal advantages. Roanoke Island—located between the Atlantic Ocean and the mainland—was selected as a potential base. In 1585, England established a military-style outpost under Ralph Lane. This first colony struggled with supply shortages and deteriorating relations with local Algonquian tribes. When Sir Francis Drake arrived in 1586, the colonists abandoned the settlement and returned to England.

Learning from earlier failures, Raleigh planned a permanent civilian colony. This time, families—not soldiers—would settle the land. Approximately 115 colonists, including women and children, sailed under the leadership of John White, an artist and experienced navigator. The colonists were meant to establish their settlement in the Chesapeake Bay area, but circumstances—possibly including the ship captain’s decisions—led them instead back to Roanoke Island. John White became the Governor of the Colony.

On August 18, 1587, Virginia Dare, granddaughter of John White, was born—the first known English child born in North America. Her birth symbolized hope that the colony would finally take root.

Trouble from the Beginning

The colonists encountered strained relations with nearby tribes, some of whom remembered violence from the 1585 colony. An early incident—in which a colonist was killed—set a grim tone. Recognizing the colony’s vulnerability, the settlers persuaded John White to return to England for supplies. Though reluctant to leave his family behind, White agreed, expecting to return quickly. The long delay: War with Spain. White’s return was delayed by events beyond his control. In 1588, England faced the Spanish Armada, and all available ships were commandeered for national defense. White attempted to return twice but was thwarted by privateer attacks and logistical failures. It was not until 1590—three years later—that he finally returned to Roanoke.

The Discovery of the Abandoned Colony

On August 18, 1590—Virginia Dare’s third birthday—White arrived at Roanoke Island. The settlement was silent and discovered to be completely deserted. White was especially concerned about his missing daughter Eleanor Dare and his grand-daughter Virginia Dare. Buildings had been dismantled, suggesting a planned departure rather than a violent attack. The only clear clue was the word “CROATOAN” carved into a post and “CRO” carved into a tree. White had previously instructed the colonists that if they relocated, they should carve the destination’s name; if under duress, they should add a Maltese cross. No cross was found. Croatoan referred to a nearby island (modern Hatteras Island) and a Native tribe known to have been relatively friendly.

White intended to sail to Croatoan Island to search for the colonists, but severe storms and ship damage forced his crew to abandon the attempt. He never returned to Roanoke.

Possible Theories

The most accepted theory is that the colonists integrated with local Indian tribes, especially with the Croatoan. Supporting evidence includes: Friendly relations with the Croatoan people. Reports from later English settlers of Native Americans with European features. Archaeological finds of English artifacts at Native sites. Some historians argue the colonists moved inland toward the Chesapeake Bay, their original destination. Archaeological work at Site X (near the Albemarle Sound) has uncovered 16th-century English pottery and tools. Disease and Starvation-The region experienced drought during the late 1580s, confirmed by tree-ring studies. Crop failure, hunger, and disease could have forced survivors to scatter or seek refuge with Native communities. Hostile Attack- While no direct evidence of massacre exists at Roanoke, hostile encounters were common. It remains possible that some colonists were killed, while others were absorbed by surrounding tribes. Spanish Intervention (Least Supported) Spain, aware of English activity, destroyed other English outposts in the region. However, no Spanish records confirm an attack on Roanoke.

Archeology and Modern Excavations

Fort Raleigh Excavations. Ongoing digs at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site have uncovered domestic items—tools, ceramics, and weapons—but nothing conclusively proving the colonists’ final fate Hatteras Island Finds-Artifacts such as a signet ring, gun parts, and European-style pottery found on Hatteras Island much strengthen the assimilation theory.

DNA and Oral Traditions

Some families in the region historically claimed descent from the Lost Colony, though definitive DNA proof remains elusive. Cultural Impact and Legacy

Cultural Impact on Literature and Folklore

The Lost Colony has inspired novels, plays, documentaries, and legends. Outdoor drama performances have been staged on Roanoke Island since the 1930s. Native American Oral Traditions and the Vanished Roanoke Settlement Roanoke occupies a unique place in American history—the first English colony and its first great mystery. The story reflects: The dangers of early colonization. Cultural misunderstanding. The limits of imperial ambition.

The disappearance of the English colony established on Roanoke Island in 1587—later known as the Lost Colony—has long fascinated historians. While English records end abruptly with the cryptic word “CROATOAN,” Native American oral traditions preserved among Algonquian-speaking peoples of the Carolina Outer Banks provide alternative frameworks for understanding what may have happened. These traditions do not present a single dramatic event but instead describe gradual absorption, conflict, migration, and survival, viewed through Indigenous social memory rather than European documentation. Indigenous perfspectives are often sidelined in traditional Non Native American Indian re-tellings.

Indigenous Peoples of the Roanoke Region

At the time of English settlement, the Outer Banks and adjacent mainland were inhabited by Algonquian-speaking nations, including: Croatoan (Hatteras), Roanoke, Secotan, Chowanoke, and Weapemeoc.These societies maintained extensive trade networks, kinship alliances, and seasonal migration patterns. Oral tradition—songs, genealogies, ritual storytelling—served as a primary means of preserving history across generations.

Among the most persistent Indigenous traditions is that English colonists were taken in by Native communities, particularly the Croatoan people living on present-day Hatteras Island. Key elements remembered in later accounts include: Light-skinned ancestors who spoke a strange language. Intermarriage between Native women and foreign men. Knowledge of metalworking which the Native Americans did not previously possess and European-style tools appearing in Native villages. Descendants with gray or blue eyes noted well into the 1700s. Rather than a rescue or abandonment narrative, Croatoan oral history frames the colonists as refugees who assimilated into Native society after their colony became unsustainable.

Chowanoke and Secotan Traditions: Violence and Dispersion

Other tribal traditions suggest a darker outcome for some settlers. Oral histories attributed to mainland groups describe: Skirmishes between colonists and Native communities after food shortages worsened. Small groups of English survivors being killed or scattered. Colonists moving inland along rivers such as the Chowan and Roanoke Rivers. These traditions emphasize that the English were no longer seen as powerful newcomers by 1587 but as vulnerable outsiders, dependent on Native goodwill.

English Accounts Influenced by Native Testimony

Later English settlers and explorers recorded Indigenous stories that echoed oral traditions: William Strachey (early 1600s) wrote of Native reports claiming that English survivors lived among inland tribes and built stone houses. John Lawson (1709) encountered Hatteras Indians who claimed descent from white ancestors and spoke of books and iron tools inherited from them. While filtered through colonial bias, these accounts are significant because they were secondhand transmissions of Native oral history, not European eyewitness claims.

Why Oral Traditions Differ from Written History

Native oral traditions do not aim for chronological precision. Instead, they preserve: Social consequences (intermarriage, alliances). Moral lessons (hospitality, conflict, survival). Collective memory rather than individual events. To Indigenous societies, the disappearance of the Roanoke colonists was not a mystery—it was a process. Outsiders arrived, struggled, and either died or became part of Native communities.

Modern Archaeology and Oral Native American Indian Tradition

Recent archaeological finds on Hatteras Island and inland North Carolina—including European artifacts found in Native contexts—have strengthened the credibility of these oral traditions. While archaeology cannot confirm individual identities, it supports Indigenous claims that English materials and people moved into Native settlements rather than vanishing entirely.

From a Native American perspective, the Roanoke colonists did not mysteriously disappear. They: Were absorbed into Native communities. Migrated inland with tribal allies. Or perished during famine, disease, or conflict. Native oral traditions transform the Lost Colony from a supernatural enigma into a human story of cultural contact, survival, and adaptation. When these traditions are taken seriously, the “Lost Colony” becomes less lost—and more remembered.

British DNA Found in American Indians of Roanoke Isle, Virginia: Untangling a 400-Year-Old Mystery

For more than four centuries, the disappearance of England’s “Lost Colony” at Roanoke has been one of North America’s enduring historical mysteries. In 1587, over 100 English men, women, and children — including the governor’s family — landed on Roanoke Island (in today’s North Carolina). When a supply ship returned three years later, the settlement had vanished without a trace, save for a single word carved into wood: “CROATOAN.” Snopes

Over the years, many theories have emerged to explain what happened to the colonists. One of the most intriguing — and hotly debated — is that they didn’t die but were absorbed into local Native American communities. If true, this assimilation might leave genetic footprints in the descendants of indigenous peoples along the North Carolina coast.

The Promise and Challenge of DNA Evidence

In the early 2000s, researchers launched the Lost Colony DNA Project — led by Roberta Estes and others — to search for genetic evidence of this integration. The idea is straightforward: if some colonists joined Native American tribes and had children, modern descendants in groups like the Lumbee or Hatteras peoples might carry traces of British ancestry alongside Indigenous DNA. FamilyTreeDNA+1

Using tools like Y-DNA (paternal line), mtDNA (maternal line), and autosomal DNA (which reflects overall ancestry), scientists and citizen geneticists have collected samples from individuals in coastal North Carolina regions. Certain families with surnames historically linked to the Lost Colony — such as Brown, Dare, and others — have drawn particular interest when European genetic signatures appear in their Y-DNA or overall genetic makeup. EarthScope

Despite this effort, no publicly confirmed, direct match between a DNA sample from a known Roanoke colonist and a modern person has yet been made. Part of the difficulty lies in the lack of reliably identified 16th-century DNA from the colonists themselves: without verified ancient DNA to compare to, even suggestive modern matches remain tentative. Snopes

Oral Traditions, Artifacts, and Historical Clues of the Roanoke Colonists

Oral histories among tribes like the Lumbee and the Hatteras recount ancestors who came “from across the sea” or exhibited features sometimes described as European. These traditions have long fueled speculation about intermarriage between colonists and Indigenous peoples centuries ago. Mshirley0+1

Archaeology lends partial support to this view: European-style artifacts — including glass arrowheads, sword pieces, and pottery — have been found at Native villages on Hatteras Island and inland sites, sometimes dating to the late 1500s. Supporters of the assimilation theory argue that these finds, mixed with Indigenous materials, reflect the presence of colonists living among Native communities rather than simple trade goods. National Geographic+1

What Genetic “British DNA” Really Means

When researchers talk about British DNA in Native American populations, they’re not implying a tidy or direct lineage. Instead, genetic traces in living people typically indicate distant ancestry — fragments of European genetic markers alongside Indigenous markers. These markers might be more common in certain haplogroups (genetic families) known to be frequent in Western Europe. Grokipedia

But DNA doesn’t tell the full story on its own. A match to a broad European haplogroup doesn’t conclusively prove descent from Roanoke colonists — it could reflect later colonial intermarriage, migration during the 17th- or 18th-century settlement period, or other contacts. That’s why researchers combine DNA evidence with historical records, surnames, oral histories, and archaeology to build the most convincing case possible. Familypedia

The Current State of the Research of Roanoke Colonists

As of 2025, no definitive genetic proof that directly connects modern Indigenous communities in the Roanoke region with specific survivors of the Lost Colony has been published in peer-reviewed science. Nonetheless, the accumulated evidence — from oral tradition to artifacts to suggestive DNA signatures — highlights a strong possibility that cultural integration and intermarriage occurred after the colony’s abandonment. The Southern Blueprint

What the research so far does suggest is this: Some Native American families in the region carry European genetic markers not typical of unmixed Indigenous ancestry. EarthScope. Archaeological finds of English-style objects in Indigenous village contexts imply contact that may go beyond simple trade. National Geographic. Oral histories align with the idea of assimilation, though they cannot stand alone as evidence without support. Mshirley0

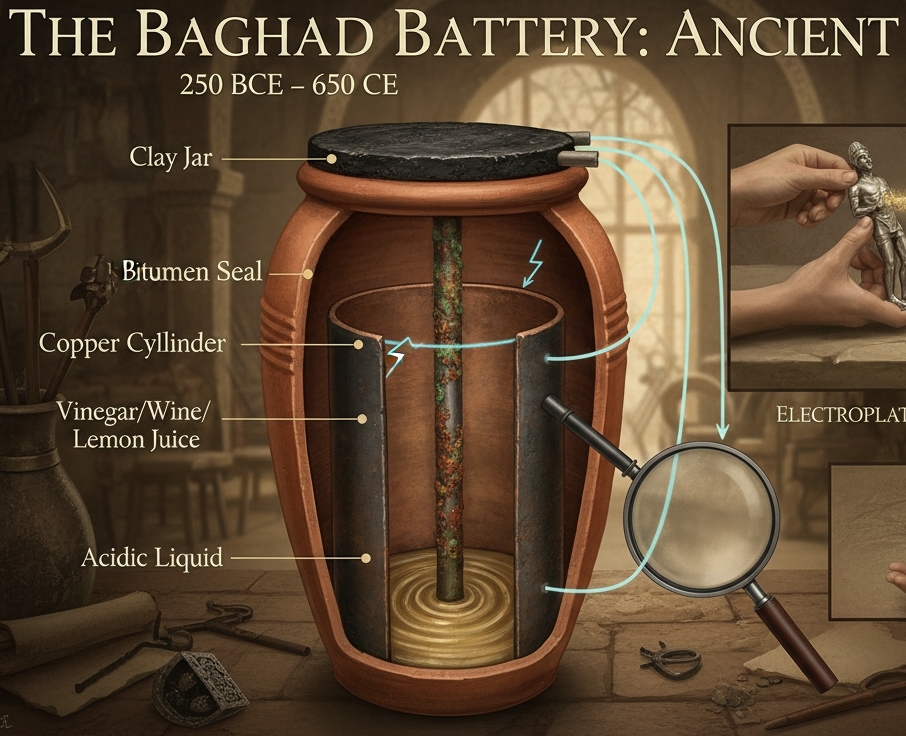

From 2015 to 2025, Mark Horton, an archeological professor at the Royal Agricultural University at England, and his crew worked with the Croatoan Archeological Society’s Scott Dawson were doing observation and research work at the middens, which are the rubbish heaps of Native American Indians that lived on Hatteras Island. The team found hammerscale which are tiny, flaky bits of iron that came from forging iron. Hammerscale is the metallic material that comes off a blacksmith’s forge. The metal has to be heated to an extremely high temperature. The British had such advanced technology while the Native American Indians did not. The hammerscale, as well as other artifacts as guns, nautical fittings, small cannonballs, an engraved slate and a stylus, in addition to wine glasses, and beads. All these relics mentioned were found stratified; underneath layers that are known to date to the late 16th century or to the early 18th century.

Furthermore, the Croatoans talked about people with blue or grey eyes that could be able to read from books. And the Croatoans said there was a ghost ship that was sent out by a man called Raleigh, apparently being Sir Walter Raleigh.

The search for British DNA in American Indian communities near Roanoke isn’t just an academic exercise — it speaks to deeper questions about identity, history, and how we understand America’s earliest encounters between Europeans and Native peoples. It challenges the simplistic narrative of separation and extinction and suggests that some of the first English settlers may have lived on, not as isolated relics but as ancestors woven into the fabric of Indigenous and later American communities.

Conclusion: Mystery, Not Failure

The disappearance of the Roanoke colonists was seemingly not a tragic annihilation. Increasing evidence suggests adaptation and survival, albeit outside the bounds of English record-keeping. Rather than vanishing into nothingness, the colonists strongly appears to have become part of the New World in a way England never anticipated. Until definitive evidence emerges, Roanoke will remain a haunting but very optimistic reminder of how fragile early colonial dreams were—and how history often leaves us with questions instead of answers.